Chapter II

The March to Arras and the Battle

The March to Arras and the Battle

The glorious cold January gradually changed to the most beastly conditions of rain and mud. My only thoughts of the march south are memories of trying to keep warm and marching on for that purpose, heavy grooming for the men, short rations, short forage, misery and mud. Nevertheless we weren’t very miserable.

Of course the horses were in the open and wise generalship (a soldier ought never to be sarcastic) had ordained that we should clip them entirely.

Note: During the march we halted at Grauches and a game of rugger was arranged. In the morning I had to “push off” to get a gun, so taking a limber I went to Bourques Maison hoping to be back in time for a late breakfast. I discovered no trace of the gun, but by means of telephone found that it was at Frévent. We “pushed on”. At Frévent while the horses watered and fed I interviewed the blue caps; I ‘made’ 1 sack oats and lots of hay, but found that the gun was only a 'piece' having no carriage. Much telephoning and labour produced a lorry and we arrived back about 9pm, late for breakfast; worse I missed the rugger.

My memories of Frévent include Hotel D’amiens and a certain young lady there, who served the wine.

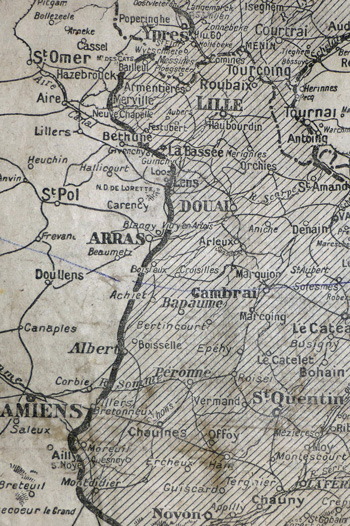

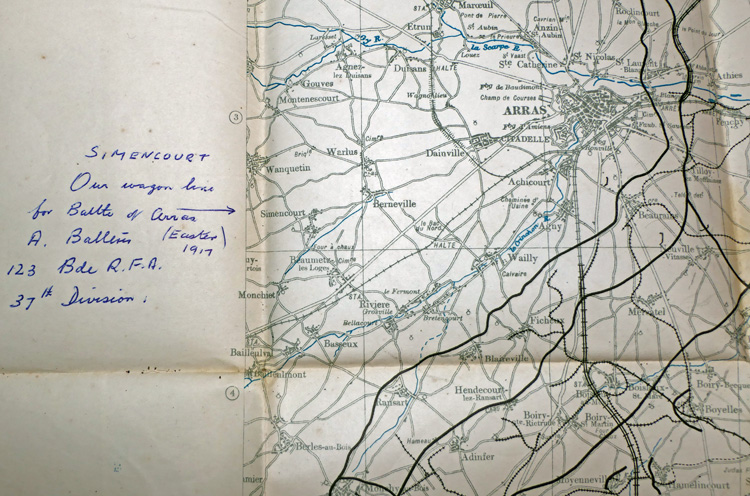

When we arrived at Simencourt (about 10km SW of Arras) they were thin and miserable nor need you imagine that Simencourt was a health resort to improve their condition. Simencourt consisted of a church, some water troughs, and some farmhouses all surrounded by slimy mud. It was very difficult to get on foot from the horse lines to the gun park, though only 20 yards. The horses, up to their knees, would cut themselves on buried corrugated iron. Work here consisted of leaving the wagon line at 9pm and arriving back (after delivering a complete échelon at the gun position near Beaurains) about 5am. This work continued until 12,000 rounds were at the guns ready for the battle. I understand that about one 18pdr for 20 yds of front was present for the battle, and that 72 9.2” hows also took part. Whatever the actual concentration there is no question that it was greater than ever before.

Note: Beaurains on the Arras-Bapaume road, about 5km from Arras. We skirted Arras and then continued on this road, about halfway to B.

I joined the guns some little time before the battle (or rather the actual attack commenced) and found that A and B batteries were messing in a house in Arras and I slept in the basement of the house next door. Some 4.5 hours made this rather difficult for they fired all night from their position about 100 yards away and I was uncertain at the time whether it was us firing or the Bosch.

As the day of attack approached, bombardments had to increase in severity and, about a week before, we all went to live at the guns in dugouts, scarcely splinter proof.

We fired from 600 to 900 rounds a day that week and as batteries were like flies it is not surprising that the Germans found it impossible to bring up food. We suffered casualties from batteries behind us including the Staff Sgt Artificer and the Officers’ Mess Cook. This was so unpleasant that all gun pits were protected by sandbags behind them and walls made for officers to stand in front of. Mine collapsed owing to rain and during the actual attack I received a blow in the back, (fortunately only mud) caused by a “premature” from behind; the body of the shell buried itself in one gun pit and the fuse in another nearly blinding the corporal with mud.

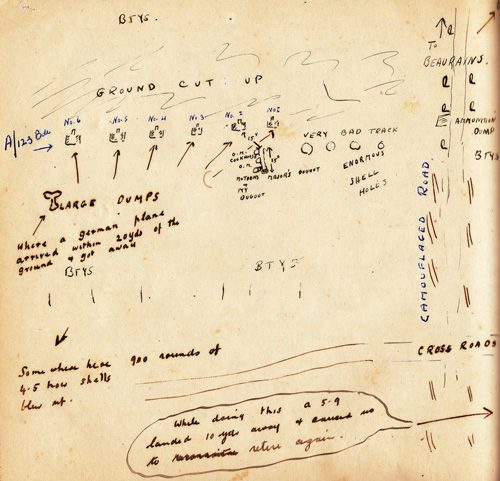

Ammunition at this position was dumped in dugouts by the guns in large quantities, five or six hundred rounds often being together. Later, 50 rounds was made the maximum owing to so much being blown up. Men walked about with sand bags on their heads, the tin helmet was not popular. The O.P. was on the right of Beaurains and walking down the main street (an old No Man’s land) one found a medley of bricks, wire and front gates. Moreover Beaurains was not a healthy spot. From the O.P. I saw a practice barrage (rehearsal for the attack) bursting on the enemies trenches.

Aeroplanes were most interesting to watch, one red German plane chased an old observation plane down by us, and came himself within revolver shot of us. The ground was too much cutup for any plane to land successfully.

During the Battle we were very fortunate. It started with a flash of guns running like lightning along the ground and then for hours a continual hubbub and buzz during which shouting was useless at 5 yards and conversation impossible. The great advantage of these battles was that noise prevented one hearing a shell come (till close) and therefore prevented one being ‘fearful’ at a shell not coming close.

After ‘Cease Fire’ Morice and I were lunching in the Mess dugout when with a roar, a ‘wump’ and a sound of falling earth, we realised a 5.9 had shown undue familiarity. Morice, in anticipation of more to come, and in realisation of our job finished, ordered the men ‘clear’, this was done hastily owing to further incentive and with much ‘chucking’ on the way. One man was found to be missing. After a short period the fire on the position itself seemed to have stopped and Major Tonkin (who arrived in the interim), Major Elliott and myself went to see what damage had been done. The first round had landed at the trail of No. 2 gun, thrown the gun out of the pit and turned it on its back. The cutup state of the ground can be imagined to some degree when I say that it took one hour to find the body of the limber gunner, though it was only about 20 yards from the gun. Previously we found small pieces of flesh and parts of kit. Prisoners were arriving all the morning along the road and everything pointed to success. The great drawback to methods employed in this and other attacks, was that the enormous artillery preparation gave the enemy warning of heavy attack, so that he decided

1. To hold the line a comparatively lightly.

2. Make the attack as costly to us as possible by arming those, whom he decided to sacrifice, with machine guns.

3. To get ready behind his line (where our bombardment did less damage) and hold this line with fresh troops against our weary ones arriving.

We retired into a farm between Achicourt and Arras (I believe) on the day after the attack and spent a pretty wretched night. The horses in the open were covered with snow and I slept on ammunition boxes left by a heavy battery.

The march from the La Bassié area had brought down the condition of the horses very much. Simencourt and heavy work on shell-broken roads had made them worse and there was an evil time to come. In addition to their miserable conditions the ration of 6lb of oats (which for a period was the issue) was insufficient and perhaps the biggest hardship of all for the horses was being clipped in January.

Photo: Signalling Station at Neuville-Vitasse, 29 April 1917 (Public Domain)

Photo: Signalling Station at Neuville-Vitasse, 29 April 1917 (Public Domain)

We advanced to Neuville Vitasse (see map above, SE of Arras) (Note Cyril added later: 37th Division memorial. Visited 1961 I think), a village of blood and ruins, another night in mud, actually lying in it, and exchange of guns and next night the most ‘glorious’ (?) march of all. The brigade was collected on the road from Beaurains to Mercatel, and at sundown we were trying to cut our way across trenched country on the left of the road. Finally we caught up the advancing infantry lying by the road (from Mercatel to Henin Sur Cogeaul) made a home where best we could with some Infantry Officers in a small shack; and sitting, there was no room to lie, we slept a few hours till dawn.

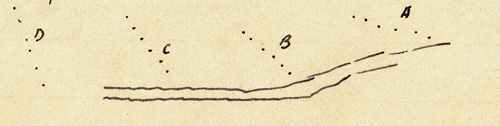

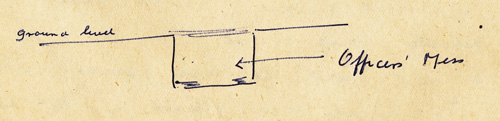

The next morning, although cold, displayed to us the first sunshine which suggested spring. One horse died of exposure and exhaustion; on we trudged. A 60pdr section had got ahead and was firing from West of Henin Sur Cogeaul; we passed through the village and up the slope in the direction of Croisilles. The four batteries were echeloned down the hill but the other three soon changed their positions though A Battery remained some time.  (Diagram)

(Diagram)

This ends my share in the Arras battle, itself a success; I have now to describe briefly the after attacks, far more costly and far less successful.

Note: The protection here consisted merely in being beneath ground level, head cover of the mess being a large tarpaulin. I remember one quiet night after dinner, when Morice and I were alone, a shell arriving and a shower of earth pouring on our delicate roof. This was the only round that night.

Continued: War Diary Chapter 3

Return to: War Diary Chapter 1