Postcard written by Cyril on 2nd June 1917 whilst on leave, addressed to Miss Yell of Balham, London. "Most comfortable journey in easy stages, am much enjoying it. Went for a walk, to place shown, this afternoon. CGH". As the card is unstamped and passed down with Cyril's possessions, it was presumably never actually posted. I wonder who Miss Yell was!

Chapter IV

My first leave, the march to Messines and life (and death) on the ridge.

Of my first leave, or any of them, I remember little. A hectic rush, no time to do anything much except spend money, and then back again. I remember that on this occasion I was glad to get back; from my second leave I did not mind returning, but afterwards I did not want to go. I found the battery, out of the line, at Hindecourt (near BOISLEUX). Sad to relate the offices were just recovering from a ‘binge’of the night before. Morice woke at midday, drank his shaving water and went again to sleep. However we were due to return to the line at once and I, soon found myself back in the old ‘funk hole’. I don’t remember the details of our fighting, barrages at absurd hours of the morning marked them chiefly on my memory. It is objectionable trying to be a hero at 04.00 hours with no spectators and an empty stomach.

One attack I remember was preceded by stunting done by five of our planes to attract the attention of sentries, just as it was getting light.

Photo: Messines Ridge June 1917. (Public Domain) Read more here about the huge significance of this ridge.

Note: we played football round the gum position, unless captive balloons were up.

My first day in the line was the occasion of a fairly narrow escape. I was walking along the battery trench with my haversack in my hand. Amongst other things in the haversack was a bottle of Citronella, which I had brought from England. Suddenly I heard an ominous sound growing until with a roar my old friend 5.9 landed on a dump of 300 shells in the trench 20 yards away. Throwing down my haversack I jumped into my funk hole as the shell completed its journey; I saw a flash across the entrance and my haversack hit by a flying cartridge case burnt vigorously, breaking the citronella bottle and causing the trench to smell for the rest of our stay. Motion, I think it was, who said, when I told him it was supposed to be a bug killing mixture, that it smelt more like a tiger killing mixture.

After this dump had ceased to be active I ran for it, with the rest of the battery, for this lucky round was the first of many.

B subsection were in a mined dugout and fairly safe, but the dump that had gone up was right at the entrance to the dugout and we were anxious for them. On being able to approach the first thing I saw was old Bellamy’s cheery face and to hear his cheery old croak, “Yes, we’re all right sir.” Bellamy was one of the type that one can merely marvel at. Well above military age he gave up driving a “bus” (horsebus) in Putney to serve; and his cheeriness and entire contempt for shells was a continual source of remark.

It was a happy day when the battery, at sundown in June, marched peacefully out. The marches, as far as the Frévent district are, however, a dim memory for, although short, they were so slow that they were infinitely fatiguing. I remember one night getting two hours sleep.

Our rest near Frévent was delightful and here I first remember “Gramophone Willy” who came to command the Brigade.

We played a cricket match, beating B Battery, I was rather pleased at being top scorer and bagging most of the wickets.

The march to Baillent-Merres and finally to Dranoutre and Lindenhock (two positions E of BAILLEUL near and on MESSINES RIDGE) was not unpleasant, but the position we occupied W of PICKWOOD was a very distasteful one. We were continually shelled with 8” day and night, we never fired, the idea of going near the guns seemed a bad one. They lay in a mass of disturbed earth, clean and serviceable but unfortunately situated. Although heavy “stuff” was continually falling closer to them it is rather curious that the only gun pit actually struck was empty. It was demolished by two 8” shells. I say “pit” there was no attempt at protection.

Photo Right: A howitzer firing during the Battle of Messines. Artillery played a huge part in fighting on the Western Front. (Wikipedia, Public Domain)

I had the joy of bringing up 1000 rounds per battery, from Lindenhock, for the Brigade. We unloaded from rail in the early evening and then loaded onto small trolleys. These trolleys were each pushed by two men and ran on a light railway up to the front. The journey seemed interminable and I arrived in the vicinity of batteries about 11pmand got the stuff delivered somehow under 8” fire. I can still hear the whizz of a large piece of shell which missed my head by inches. Some of ours was blown up before the morning was very old. Sgt Powell and others rather stoutly extinguished the ‘camouflage’ which was set alight.

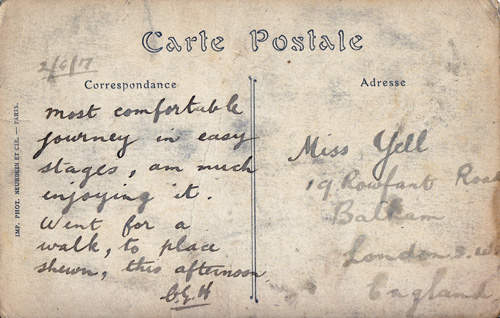

We prepared a new position near “Petits Puits” (Messines Ridge) and got up ammunition. About this time I recollect many dark nights on the road and everyone giving a hand to get the shells dumped and the teams back home. Fortunately Roberts brought up the teams and with him in front the drivers would have gone to L------ without hesitation.

We got very slippy at getting the ammunition from wagon to dump in a man-to-man chain.

The “Petits Puits” position was a lucky one in some ways, and very unlucky in others. We had 10 guns blown up in three weeks, but casualties were not very heavy. There were several incidents of interest. Gr----- was walking along H Battery trench when a whizz bang exploded by his side. He cried, “I’m hit, I’m hit” and was soon seized by willing hands. On taking down his trousers to see the extent of his injuries he was as surprised as anyone to find himself unhurt.

Once, when firing, an 8” shell came with a terrific roar and burst in front of No 4. The next went over and killed a man in A/124 Battery behind the third landed 2 yards from Motion - who was miraculously saved - but wounded several men on No 4 gun, some fairly seriously.

On another occasion when firing on an imaginary S.O.S. a gun about 15 yards from me blew up, owing to a break of the mainspring of the firing mechanism, a wedging of the firing pin in the metal of the firing hole bush thus causing a cartridge to be fired as the breach closed.

The No 1 was wounded in the stomach, Nos 2 & 4 lost arms but No 3 who was closer than anyone escaped with shock and minor injuries. I brought the wounded to GUY’S FARM where they were tended by an American doctor who cut off arms while he chatted to the patients. No 2 died later, but the others survived, two of them to fight again.

We were very frequently under heavy fire and had our first serious introduction to gas. Horses waited at the gun position with respirators on! We owed the small number of casualties to the way in which the battery was spread out. Frequently the whole battery except the telephonists, who had excellent protection, would have to “run for it”, as when firing was not required there was no point in staying to be “wiped out”. I was blessed with the power to sleep whatever happened, the value of youth. Many unfortunate fellows couldn’t sleep if there was “anything” flying around.

I wasn’t sorry to leave Messines and go on a course of gunnery, at Tilques, near St Omer, situated in a most wonderful country of golden corn. Here I had a most delightful time on the canals, playing tennis and generally forgetting the war. When visiting the aerodrome at St Omer where we received instruction, including the study of aerial photographs, we travelled by motor bus.

I and many others were on top and were surprised by a military telephone wire, hanging low. We all avoided it except one fellow who, got temporarily “knocked out” by it and was “out” for an hour though apparently conscious.

At our farewell dinner to our instructors I and another fellow arrived too early. We returned later to find this time we were late. As penance he made a speech and I had to recite “The Yarn of the Nancy Belle” (by Gilbert). We drank too much!

Photo: The Battle of Messines 1917 has been described as the forgotten WWI victory that changed the British Army. It was the first battle when tanks went head to head.

Note: Recollections of the artillery school, Tilques, 1917

The country in the neighbourhood of Tilques was all the more enchanting in contrast to the stricken battlefields. In addition we were blessed with most glorious summer weather and the wheat was in full glory. Skeleton driving drill frequently took us out to see the beauty of the country. The numerous beautiful little canals on which we punted or sculled amidst water lilies and luxurious green, added to our general enjoyment, while we were able to visit St Omer by motor bus in the evenings if we desired. Most of the officers were Australians and good fellows we found them.

When I returned to my battery it was to a position known to us as “The Quiet Position” as we hardly got shelled at all.

Soon we moved to the Ravine Wood position in an area where much fighting had taken place early in the war.

Note: Hill 60, Shrewsbury Forest, Battle Wood, Fusilier Wood etc. Hollibeki & Verbranden-Molen. The Ravine Wood position was a few miles S of the MENIN ROAD and SE of Ypres.

Photo: Soldiers loading a 155mm Howitzer near Meuse, France, 1918. (National WW1 War Museum - Educational/Research use)

It was autumn and winter again, but everywhere, no road to the guns, only a light railway. Even guns had to be moved on the light railway. Ammunition was brought up, with difficulty, on pack horses, one of whom fell into a deep trench and we got him out safely. Our dugouts were splinter proof, perhaps, and were alongside a trench with duck boards.

I wrote to a daily paper to ask for a football, in anticipation of going out to “rest” on some future date. One day I left the football in my dugout, and was absent for two or three days, living in an O.P. somewhere near HULLEBEKE. It was a very strong pillbox, with 8 feet of concrete overhead. When I returned I was disconsolate to find that my dugout had received a direct hit, and the football was in fragments.

It was in this position that I remember we reported that about 3000 gas shells fell around us one night.

On one occasion when I had been engaged with some of the men round the battery; I think moving a gun; that I remember a large piece of high explosive shell passing between me and Sgt McLean, who was a yard or two away. We smiled at one another, and that was that.

The guns were in pits, sandbags and corrugated iron. It was routine here as elsewhere to test the sights of guns frequently.

One day, when I was doing this, the limber gunner of No 1. removed the firing mechanism for me, and I looked through the hole in the firing hole bush, but found that it was not clear. I asked him to clear it, so he replaced the mechanism, thinking that oil had blocked up the hole. He was leaning on the gun when he pulled the trigger, there was a flash and roar and he disappeared through the door of the gun pit.

When I got to him he was bleeding at the mouth, but fortunately had no serious injury, and was at work next day. He had forgotten that his gun was ready loaded for sniping purposes!!

I had a lot of night observation work, at various O.P’s and was wounded one night - by a sardine tin! I still have the scar, very clear 40 years after. We got a good deal of shelling, including gas and very unpleasant it all was. One night we had a vast number of gas shell falling around.

Our next move was to HOOGE, though there was no sign of the village, except an occasional piece of a house in the mud; but only a small piece. During this period the battle at Passchendaele was in progress. Passchendaele is 8,000 yds from HOOGE.

The Battery position was close to the MENIN ROAD, which, being destroyed and obliterated, was made up with wooden planks. At one time all six guns were together, and at another time for of the guns were off the southern side of the MENIN ROAD towards SANCTUARY WOOD.

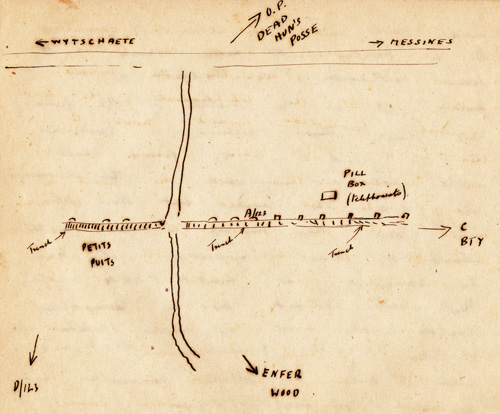

The officers mess considered of a cupola covered with earth, and would not have kept out the smallest shell. In fact one of our predecessors there was wounded by a shell, losing an arm while lying in bed. The only real protection available was in a small PILL BOX which was used by the signallers.

The top of it was level with the earth, and a pump had to be used continually to keep down the water level.

One day when I returned from leave I walked up the MENIN ROAD and found the Battery was being shelled. I waited until the shelling stopped, and then walked to the Officers Mess. Later the Colonel arrived and soon the shelling recommenced. It came from a heavy howitzer and the sequence was as follows:-

One day when I returned from leave I walked up the MENIN ROAD and found the Battery was being shelled. I waited until the shelling stopped, and then walked to the Officers Mess. Later the Colonel arrived and soon the shelling recommenced. It came from a heavy howitzer and the sequence was as follows:-

a. A grunt from far far away.

b. A slow and laboured climbing of the projectile until it got “to the top”.

c. An increase in speed until there was a roar like an express train and a violent explosion.

When one of these came so close that large lumps of earth reached the entrance to the little shack in which we sat, the Colonel asked us if we hadn’t got a “better place”! Five of us therefore, including the Colonel, hurried over to the signallers’ PILL BOX and sat down below.

The rest of the battery, NCOs and gunners had been sent over to B Battery until the shower was over.

We had not been in position long before a heavy shell landed on the ground outside, near enough to close in all the area shown as steps, and to obscure our view of daylight except for one small hole. Water came at us from the ground and from above. All telephone wires were broken except two. (Illustration below)

We sent through a message asking to be dug out when the blitz had finished. Some little time later we heard a voice from above, using colloquial expressions, when Sgt Lester saw what had happened and we were soon up and about.

I got to know the trenches astride the MENIN ROAD and the forward posts. It was from one of these posts that I observed a bombardment of POLDERHOEK CHATEAU by guns of all calibres. The Château was a very large mound, with HUNS in the cellars.

1918 (Written 1965)

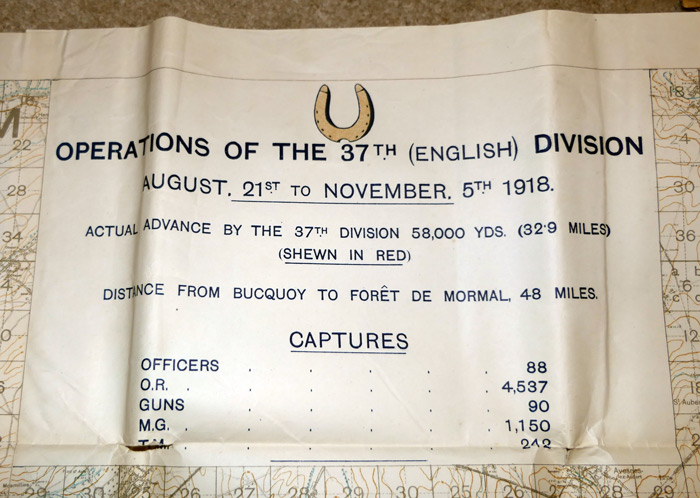

A/123 and the rest of the 37th Division Artillery 123 & 124 Brigades were still in the Salient when the Germans opened their powerful attacks in March and April. But these attacks, as shown in the list of battles, were in the southern part of the British line and are included under the heading, “The Offensive in Pacardy” 1918.

Day by day we heard of the German advances and wondered when the 37th division Artillery would be moved down. 37th division Infantry were moved down but it was a long time after that we were moved. So late was it in fact that the German attack in the South had petered out. It must have been very early in April 1918 to the German attacks in the parts of the line which we were living began about 9th April. They advanced and captured places through which we had moved about 48 hours previously, on the line of march. The Battles of the Lys.

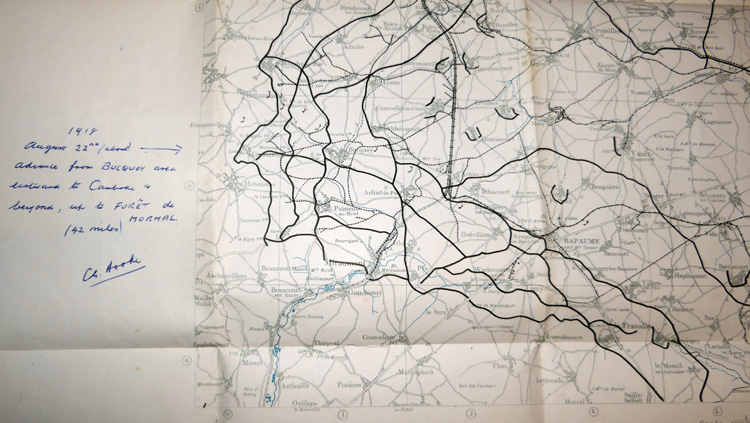

But we were destined for the Doullens area and I remember wagon lines in the vicinity of SAILLY AU BOIS & HÉBUTERNE, east of DOULLENS. After a time I remember we marched for a time down to the French sector and then back again to come into action in the area HANNESCAMPS; with ABLAINZEVELLE & BUCQUOY held partly by us and partly by the Germans. It was from this area that the 42 mile advance to victory in this sector was to begin in August 1918.

Amusing incident?

Not very far from HANNESCAMPS my kit was on a mule. We came under fire and mule did not like it. His first stop was at the wagon lines 9 miles away! (With my kit still intact)

When we had come into action in the early morning we came under heavy fire, as did another battery in front of us. We watched them being given a terrible “pasting”. Old Bellamy (Putney horse ‘bus driver) instead of running for cover sat on gun seat and filled his pipe.

Before the opening of the offensive, batteries moved up to advanced positions thus obtaining greater control even after the Germans retired.

In August the barrage opened with great intensity and the attack began. As usual we suffered from shelves of our own Artillery behind us which burst prematurely. I remember once looking round and seeing a mass of metal coming through the air. Soon there was quite a considerable traffic passing behind us, prisoners one way, reinforcements the other, and ambulances both ways.

That night we advanced, marching through BUCQUOY in the darkness and came into action.

That night we advanced, marching through BUCQUOY in the darkness and came into action.

Fighting continued from 22nd of August until 10th of November.

The tragedy of BIHUCOURT (click on map twice to enlarge)

As I was in charge of the battery and the teams came up to take the gun for a further advance, one isolated high velocity shell suddenly flashed on to us, killing 12 men and 15 horses, including my famous black gun team. My own horse, being held by a groom, was also killed.

The Wheelers of this gun team were two fine horses named John Bull and Mrs Bull. The team had recently been stopped on the road by a General and commended for their smart turnout.

This is the end of the Diary.

Cyril's letters home to his family from 1917-1918 provide a more detailed account of the final attacks of 1918 and the events around the Armistice of 11 November 1918.

Next: Letters from the Front 1917

Next: Letters from the Front 1917

Return: War Diary Chapter 3